Friday, March 23, 2007

Nominalization in Marathi

Chinmay Dharurkar

Definition and scope of the term:

Nominalization proper means "turning something into a noun"(Comrie & Thompson 1985) and refers to the corresponding processes

or operations and to their results.

Nominalisation covers a broad range of transposiational phenomena, where transposition in turn refers to word-class-changing operations

(Haspelmath, 2002)

Often applied without clear criteria and definitions the term [nominalisation] is grossly misused.

A clear definition of nominalisation and any serious attempts to approach them cross-linguistically should take into account at the least the following parameters:

1. What expression types are turned into a noun?

2. What are the meanings of the resulting expressions?

3. In what sense is the resulting expression noun?

4. Is the process derivational or inflectional?

5. Do the resulting expressions show mixed properties?

6. What are the functions of the resulting expressions?

With this much in the mind we will proceed to see how much productive is Nominalization in Marathi.

1.Verbal nouns: These are the nominalised forms of the verbs that are (under the influence of Sanskrit grammatical tradition) called krudanta nouns. Krudanta nouns in Sanskrit are formed as gam (to go)-gamana (going), bhASh (to speak)-bhAShaNa (speaking or speech) etc. These are also referred as ANs or action nouns.

This type of nominalization is very productive and the meaning of the resulting noun is predictable i.e. the act of V or way or manner of performing the action. Some examples of the type are as follows:

Verb Noun

1) zaa zaaNa

(to go) (going)

2) Ye yeNa

(to come) (coming)

3) zhop zhopNa

(to sleep) (sleeping)

4) vichaar vichaarNa

(to ask) (asking)

5) c^aav c^aavNa

(to bite) (biting)

Used in sentences:

1a)to gelaa he malaa paTla^ naahii.

He go-past this I-dat like-past neg.

I didn’t like that he went.

1b) tyaac^a zaaNa malaa paTla naahii

His going to me liked not

I did not like his going.

2a)to saarkhac^ hasto he c^aangla^ naahii.

He always laughs this good not is.

2b)Tyaac^a saarkha hasaNa^ c^aangla naahii.

His ever laughing good not is.

His laughing always is not good.

Each and every verb can undergo this kind of nominalization. One interesting point to note about these nouns is that these normally cant come in the main clause but nowadays there is tendency in languages like

Marathi, Hindi etc that these forms can be used in main clause position in back grounded portions of discourse. E.g. setting the scene or subsidiary information.

2. Agentive nouns: These are productive but are actually the future participle of the verbs. Or might be a co-incidence that the active future participle forms

And the agentive forms have the same phonological shape.

Some examples:

Zaa - zaaNaaraa

(to go) – goer

Ye - yeNaaraa

(to come) (comer)

Zhop- zhopNaaraa

(to sleep) (sleeper/one who sleeps)

Vichaar- vichaarNaaraa

(to ask) asker

C^aav- c^aavNaaraa

To bite biter

Such nominalisation is also highly productive.

3.Objective nouns: These are actually the passive forms of the above participles but are used as nouns. So also the process is equally productive except for the intransitive verbs.

Examples:

Vichaar- vichaarlaa zaaNaaraa

(to ask) (the one being asked)

Maar maarlaa zaaNaaraa

(to hit)- ( the one being hit)

4. Adjective to nouns:This is again a very productive one. All adjectives can be nominalised using this nominal suffix – paNaa. The meaning of the resultant expression is the property of or quality of being that.

Examples:

veDaa veDepaNaa

(mad) (madness)

aaLshii aaLshiipaNaa

(lazy) (laziness)

shahaaNaa shahaaNpaNaa

(wise) (wisedom)

Muurkha muurkhapaNaa

(foolish) (foolishness)

Naazuk naazukpaNaa

(tender) (tenderness)

Bahiraa bahirepaNaa

(deaf) (deafness)

Sopaa sopepaNaa

(easy) (easiness)

khoTaa koTepaNaa

(false) (falseness)

Lahaan lahaanpaNaa

(small) (smallness)

GoD goDpaNaa

(sweet) (sweetness)

And so on the process is productive. For Sanskrit loan words paNaa is also replaceable by the suffixes twa and taa.

Other nominalising suffixes are vaa (not much productive) found in:

goD goDvaa

(sweet) (sweetness)

Gaar gaarvaa

(cold) (coldness)

ii in :

Laayak laaykii

(eligible) (eligibility)

Laal laalii

(red) (redness)

goD goDii

(sweet) (sweetness) But not in other taste-words.

5. Nouns to nouns:

Common nouns are changed in abstract nouns by adding the suffix paN.

Not much productive. If we stretch it to all common nouns the resultant expression are possible but not found in the language and can be employed in philosophical debate in Nyaya system of Indian philosophy while discussing about jaati or category.

Examples:

maaNus - maaNuspaN

(man) (humanity)

Dev devpaN

(god) (godliness)

Replaceable by twa for Sanskrit loan words.

Also the suffix –ii acts nominalises a noun:

Maalak - maalkii

(owner) (ownership)

Gulaam - gulaamii

(slave) (slavery)

Naukar - naukrii

(servant) (service)

Praadhyaapak praadhyaapakii

(professor) (professorship)

Gaayak - gaaykii

(singer) (singing or type of singing)

ki in:

maastar - maastarkii

(master) (profession of Master)

paaTil - PaaTilkii

( a title for who owns or controls a village.)

References:

1) Brown K, (2006) Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics, Elsever, London.

2) Chomsky, Noam. 1970. "Remarks on Nominalization." In: R. Jacobs and P. Rosenbaum (eds.), Readings in English Transformational Grammar, Ginn, Waltham, MA, 184-221.

3) Mathews, P.H (2003) Dictionary of Linguistics, OUP, London

Sunday, February 04, 2007

Duals and Comparatives:An e-mail conversation

bookish forms rarely used: sundartara,sundartama etc)

Dear Chinmay,

The facts, and the evidently non-random correlation between them seem

very interesting. This line of research may have a lot of promise. Try

posting your query on the Linguist List, so that linguists speaking

diverse languages get to see and respond to it. I myself do not have

that kind of encyclopediac knowledge.

Best, G.

hotz, hotzage, hotzena, hotzege 'too cold'.

Hungarian, a FennoUgric language, uses a vowel harmonic -abb/ebb suffix on adjectives -- and nouns -- to form a comparative. Thus

Janos - NOM magas-abb mint Istvan-NOM. 'Janos tall-er than Istvan.'

An alternative form uses the harmonic suffix -nal/-nel on the noun that refers to the standard, as in

Janos magasabb Istvan-nal..

This suffix is the adessive case and means 'nigh unto, close to', so what the latter (there's a comparative with the -er suffix) sentence means literally is 'Janos is tall-er near to Istvan.'

Hungarian can also derive a comparative adjective from a noun with the -abb/ebb suffix. The noun meaning 'fox' is roka. The sentence Janos rokabb Istvanal. means literally 'Janos fox-er Istvan-next to [is].', i.e. 'Janos is foxier than Istvan.'

Now, I believe that comparative Uralicists have evidence to reconstruct this kind of system for *ProtoFinnoUgric, and possibly for *ProtoUralic. So it may have once been more widespread.

But the -tero suffix meaning 'opposite, alternate' is etymologically related to the comparatives of adjectives in some IE languages. In Greek and Indoiranian it came to mark the comparative degree, and in Irish Gaelic the equative degree, as in luath 'swift' but luathither 'as swift'. This suffix may be cognate with the -ed suffix in Welsh used for the equative degree, as in gwyn, gwynned, gwynnach, gwynnaf 'white, as white, whiter, whitest', but I do not know that it is.

U of Cincinnati

Department of Anthropology

Kindly comment to this mail.

I'm still not sure I am following your questions or proposals, but I'll try. Comments are inserted below after what they are commenting on.

At 12:51 PM 1/23/2007, you wrote:

Sir,

thank you so much for your edifying reply.

what I mean by:

"some relation between the duals and the comparative degree forms"

is:

Note that comparative form is nothing but a way to compare between two.

But actually, in many languages the comparative and superlative are not formally distinguished in any way.

And what about other degrees of comparison, excessive, insufficientive, equative, superlative, absolutive ( e.g. outermost in English.).

And even so, that does not mean there has to be a morphological or syntactic relationship, either synchronically or diachronically (historically) between the two. Dual marks a noun. Comparision of adjectives is a rather different device.

Why such special treatment by giving morphological (against analytical) suffixation in case of adjectives(Sanskrit:sundaratara,uttara,uttungatara etc.) or pronouns (anyatara,itara etc) for comparison between two?

Well, that's like asking why Khoisan languages have clicks since others don't or why a few languages have VOS order when most others don't. In general, we don't know. Some things that are rare nonetheless do exist. We would like to know why but usually it is difficult or impossible to find out why. And remember that in science, why really means "how it came to be". But as I noted, morphological suffixation to form the comparative and superlative, and equative (Celtic) or excessive (Basque) is not confined to Indoeuropean languages. Hungarian and some other Ugric languages have it, Basque has it. It does seem to be confined to Europe and Western Siberia.

Interestingly and obviously enough, such forms are found in the

languages-- Pro-to of which had duals....do u have any such example...when pro-to doesn't have duals but the modern developments of which have separate comparative form?

No, I dont happen to have any such examples. But that does not mean that dual number and suffixed forms of adjectival comparison are related phenomena. Dual number is fairly widespread. A number of languages in several different language families have it or have had it. But special suffixed forms of adjectives for degrees of comparison is far less common than dual grammatical number. (Incidentally, I don't think Basque has a dual number, but whether it did in the past I dont know and doubt if anybody does.) So having dual number is certainly not a sufficient cause for a language to develop suffixed degrees of comparison. Proto Uralic and Proto Indoeuropean both apparently had dual number. But it has been lost in Modern Hungarian but the suffixation of adjectives is very much alive. The same is true for Indoeuropean languages -- the dual number is much more restricted and vestigial but in the languages that have a suffix showing degrees of adjectival comparison, it is very much alive and productive (English, Russian, German &c. ) So one is very suspicious of positing a relationship between dual number, much of which once was, and suffixed comparison of adjectives, which very much still is. One is particularly hesitant to posit such a relationship when the sample size of languages with suffixed comparison morpheme is so very small and geographically proximate. It's just not a big enough sample to build much of a theory on.

( If so it is exceptionally interesting?)This is precisely what I mean by 'some relation'.To rephrase in other words:

Existence of morphologically affixed comparative forms for adjectives has direct relation with the existence of dual number for nouns.

But you have to have evidence that there in fact is such a relationship. You dont have any such evidence that I can see. Or,if you have, it is very weak. You have two language families -- Indoeuropean and Uralic -- in which there was a grammatical dual and in which there is found morphological marking of degrees of comparison of adjectives -- not just the comparative degree, but other degrees too. But there are many languages in which grammatical dual is found. The only other language in which there are suffixes showing adjectival degrees of comparison that I know of is Basque. That's not enough of a sample rule out coincidence as a likely explanation.

Also if this is not jabbering of mine:

With this as a point of departure we can trace the evolution of

counting numbers from 1,2 and their traces left in existence of duals and/or comparative forms.

I'm sorry, I don't follow this at all. We can find out about the development of words for numerals in lots and lots of languages. The occurrence of particular forms of nouns with particular numeral words may be an indication that there was an old partitive in a previous stage of the language, an old dual, or some other phenomenon.

And keep in mind that a few languages have a grammatical trial or paucal (a few) number in addition to a dual and a plural.

Joseph F Foster

Link to submit a question to Ask A Linguist on linguist list:

http://linguist.emich.edu/ask-ling/index.html

Tuesday, January 23, 2007

बिन हाथों में हाथ लिये

बस्स आओ बैठें बात करेंगे

बिन हाथों में हाथ लिये

एक दूसरे के साथ रहेंगे

ज्ञात है मुझ को अच्छा-

दो चार बातें तुम मुझ को नीजी सुना देना

कुछ ऐसी बातें सुन लूं तुम से

दीदी से

एक मैं ही तो हूं जो जानता हूं यह बात

Notes: MEANING & TRANSLATION

Notes: MEANING & TRANSLATION

W.V.O. Quine

1. Stimulus Meaning

1.1 Empirical meaning:

a) Is that which remains when we peel away the verbiage of a given discourse together with all its stimulatory conditions

b) Is that what sentence of the totally alien SL have in common sentences of TL and.

This ISOLATED Empirical meaning will give a language of logic.

To give meaning is: to say something in the home language that has it.

1.2 Radical Translation: is translating a hitherto unknown language into a known language.

In case of related languages (like languages of the same family or that have some kind of convergence or have same religious or cultural background etc) the translation is aided with resemblance of cognate words etc.

But for the real nature of the empirical meaning we must look into the translation of the unrelated languages one of which should be a hitherto unknown language. Translation involving such a language is called the radical translation. So for nature of meaning we should think of radical translation. It is here where the real empirical meaning detaches itself from the words that possess it.

1.3 Methodology for the translator (or linguist’s power of intuition)

He (the linguist) must be able to:

Guess what stimulation his subject is heading to-not nerve by nerve-but the rough & ready references to the environment,

Guess whether that stimulation actually prompts the native’s assent to or dissent from the accompanying question,

To rule out the chance that the native assents to or dissents from the questioned sentence irrelevantly as a truth or falsehood on its own merits without regard to the scurrying rabbit which happens to be the conspicuous circumstance of the moment.

1.4 Occasion Sentence Vs Standing Sentence:

The contrast is based on the notion of prompted assent and dissent which we are supposing available.

A sentence is an occasion sentence for a man if he can sometimes be got to assent to or dissent from it, but can never be got to unless the asking is accompanied by a prompting stimulation. (So here the asking is accompanied by a prompting stimulation is necessary.)

In other words an occasion sentence commands assent or dissent only when prompted all over again by current stimulation.(Ex. So as to know what Gavagai means we need to point out the rabbit and ask if it is. Here asking is: ‘if it is a rabbit’ (or rather Gavagai) and the rabbit’s really being there is the prompting stimulation).

No such prompted sent and dissent for the standing sentences is required. Here the subject may repeat his old assent or dissent unprompted by current stimulation when we ask him on later occasions. ( So repeatability and unprompted-ness distinguish standing sentences from the occasion sentences. Ex. There are brick houses on the elm street etc.)

1.5 Affirmative Stimulus meaning of an Occasion sentence ‘S’ is the set of all the stimulations that would prompt him to assent to ‘S’.

So also the Negative stimulus meaning of an occasion sentence ‘S’ is the set of al the stimulations that would prompt him to dissent to ‘S’.

On the conditional would prompt:

The strong conditional defines is a disposition in this case a disposition to assent to or dissent from S when variously prompted. The disposition may be presumed to be some structural condition, like solubility or more particularly, like an allergy, in not being understood.

2. The inscrutability of terms:

2.1 Meaning: Is not there in the words separately but it emerges when a whole sentence is uttered, as the words, when not learned as sentences, are learned only derivatively by abstraction from their roles in learned sentences. So also there are one word sentences as ‘White’ or ‘Rabbit’ do exist. But sentences too are highly interlinked, so is the meaning within the sentences.

So can we reasonably talk about the meaning irrespective of sentences?

Therefore stimulus meaning is devised

2.2 Notion of stimulus meaning:

It isolates sort of a net empirical import of the various single sentences without regard to the containing theory, without losing whatever it owes to the theory.

It is a device contrived while broaching an alien culture, and relevant also to an analysis of our own knowledge of the world.

2.3 Term and Sentence:

Terms have extensions to objects.

Stimulus meaning is in theory a question of direct surface irritation.

Synonymy of sentences not terms:

It is only the sentences that can be synonymous not the terms.

Sentences are not the real mediators of all the implications what a term in an untouched language has-but sentences only render some idea within the pattern of the target language. In radical translations (a) terms can never be synonymous (b) there can only be synonymy of sentences not of terms.

2.4 Inscrutability proved:

Occasion sentences and stimulus meanings are general coin, whereas terms, conceived as variously applying to objects in some sense, are a provincial appurtenance of our object-positing kind of culture. There cannot be any basic alternative to our object-positing pattern. There cannot be any in translation either, as it imposes our pattern.

3. Observation Sentences:

(Same as the summary given by Dr. Bhat Padikkal)

4. Intrasubjective synonymy of occasion sentences:

Apart from the stimulus meaning-which is unique for each individual sentences-some sentences can be synonymous.

So Bachelor & Soltero may be synonymous for a bilingual.

Intra-subjective synonymy is in principle just as objective as discoverable by the outside linguist as is translation. He may find synonymous sentences without their translations.

Even here the terms (say Bachelor and Unmarried man) need not be co-extensive general.

Talking of occasion sentences as and not as terms, however, we see that we can do more for synonymy within a language than for radical translation. It appears that sameness of stimulus meaning will serve as a standard of intra-subjective synonymy of occasion sentences without their having to be observation sentences.

There is no limit to the length of sentences and their synonymy.

5. Truth Functions:

The fact that logic of a language and the language of logic may be different (only the former i.e. logic of a language may differ from the later as we can fix the language of logic) is at the heart of this subsection. The main question is how logical concept is different form logic of a language. Logic creeps in because: is it so that all languages share same logic?

For a language that has the object positing kind of schema and that which is without such a pattern – for both the speakers of two different languages the stimulus meaning can just be the same. So the truth-functional part is the only part the recognition of which, in a foreign language, we seem to be able to pin down to behavioral criteria (i.e. speech).

6. Analytical Hypotheses:

Here we imagine a project undertaken by linguist of infinite semantic correlation of sentences. Only conjectural equating of parts may be called analytical hypotheses.

The main idea here is that there cannot be any complete hypotheses as such a guide or a handbook of translation, say from jungle-to-English. The linguist is bound to fail in the project and will come up with disdainful of English parallels to the jungle language.

He can of course do it as a bilingual. But a bilingual too does it as a split personality.

7. A handful of meaning:

It is by his analytical hypotheses the linguist implicitly starts the grand synthetic hypotheses which is his overall semantic co-relation of sentences.

No sense is made of sameness of meaning of the words that are equated in the typical Analytical hypotheses. There is no objective matter to check the nicety of the hypotheses.

A sense is after all given to sameness of meaning of the expression.

This indefinability of synonymy by reference to the methodology of analytical hypotheses is formally the same as the indefinability of the truth by reference to the scientific method. Also consequences are parallel.

The methods of AH is a way of catapulting oneself into the native language by momentum of the home language.

The analogy provided by the AH is no way unique as the relation between two analogous

Sentences is not just unique and singular, there can be many analogous sentences ( still failing to carry the import of the jungle language sentence) that analogy, therefore, cant be seen as the meaning.

Quine is not simply saying that we cannot know the meaning of a foreign sentence except as we are prepared to offer a translation in our own language, but more that:

It is not only relative to an in large part arbitrary manual of English sentences and then only in a parochial sense of meaning, i.e. use in English.

So is the indeterminacy of translation at the heart of the Quine’s essay.

Monday, January 22, 2007

`कितवा' हा शब्द आपण मराठीत जरी सर्रासपणे वापरत असलो तरी अन्य कित्येक भाषांमध्ये या प्रश्नार्थक-सर्वनामासाठी पर्यायी शब्दच सापडत नाही.हिन्दी,इंग्रजी,अरबी अशी भाषांची यादीच बनवता येईल ज्यांत `कितवा'ला पर्याय सापडत नाही.मराठीत `कितवा' जसा आहे तसा गुजरातीत केटलामो,कन्नड मध्ये एष्टनेय,तेलुगूत एन्नोवं,फ़ारसीत चॅन्दोम,जर्मनमध्ये वी फ़िल्टं इ. भाषांत चपखल पर्याय सापडतात.

(अ)संस्कृतात `कतम' हा शब्द `कितवा'चा पर्याय म्हणून लोकप्रिय असला तरी त्यासाठीचा चपखल शब्द `कतम' नसून `कतिथ' आहे - हे (पाणिनीय सूत्रे व संस्कृत साहित्यातील उदाहरणे म्हणजेच `कतम' व `कतिथ' चे आढळ उद्धृत करून) साधार स्पष्ट करणे हा या शोधनिबंधाचा एक हेतू.

(आ)बरेच कोशकार`कतिथ' या शब्दिमासाठी इंग्रजीत`हाउमेनिअथ'/`हाउमेनिअस्ट'(मोनिअर विलिअम्स,२००३/१८९९:२४६) असा कृतक शब्द निर्माण करतात.त्याप्रमाणे हिन्दीसाठीही कोशकार `कितनवा'(सूर्यकान्त,१९८१) अशी शब्दनिर्मिती करतात.या निबंधात या गोष्टीचाही शोध घेण्यात आला आहे की इंग्रजीतील fourth, fifth, sixth यातील `-th' हा प्रत्यय व संस्कृतातील चतुर्थ, षष्ठ, कतिथ व कतिपयथ यातील `थुक्'(पाणिनीय संज्ञेनुसार)प्रत्यय म्हणजेच `थ' हे सजातीय (cognate) आहेत काय?

(इ) १.क्रमवाचक(`डट्'चा तमडागम)

(ई)"तरभाववाचक रूपे व द्विवचने (एखाद्या भाषेत असणे) यांत संबंध आहे काय?" हा प्रश्न व त्यावर काही निश्चित उत्तर देण्यासाठी येणा-या अडचणी,यांचाही विचार या शोधनिबंधात करण्यात आला आहे.

Howmanieth

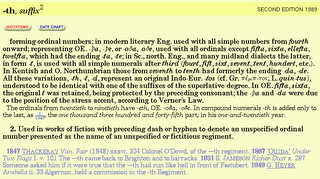

This post has to do with the first post on this blog:

A linguistic study of howmanieth.

So this is a copy of the '-th' suffix form the Internet

Edition of OED Oxford Etymology Dictionary.I am thankful

to Dr.John Smith for the same.This copy has been received

from him though an email conversation.

Please click on the image to maximize so that it can be

read with ease.

शाब्द

About Me

- चिन्मय धारूरकर/Chinmay Dharurkar

- मी एक आपला साधासुधा बर्यापैकी सुमार असा भाषाविज्ञानाचा विद्यार्थी! बाकी एखाद्या Definite Description चा निर्देश माझ्याने व्हावा असले काही कर्तब आपण गाज़वलेले नाही. हां, एवढं कदाचित म्हणता येईल की मराठीतून आंतरजालावर शीवर लिहणारा पहिला...